One of the innovations created by Four9 Design is our high-quality vacuum environment. Many low temperature experiments depend on a clean experimental space. This is especially important in systems that have delicate surface geometries or operate over longer durations.

Methods for creating a vacuum

Some cryostats create their vacuum by using a roughing pump to reduce atmospheric pressure by a few orders of magnitude, then rely on cryopumping, or freezing out the remaining gas in the vacuum space onto a cold surface. While this approach is simple, there are a lot of molecules left over to freeze off somewhere. An everyday example of this is when you take a steamy shower. The warmer vapor condenses out on your relatively colder mirror and shower room walls. Imagine the same accumulation on the inside surfaces of your cryostat.

To improve the vacuum level, a secondary higher performance pump such as a scroll pump or turbo-molecular pump can be used to reduce the molecular count even further. When choosing a support pump, you need to consider if the pump will introduce oil contaminants, vibration, or electromagnetic fields into your experiment.

Ultimately, cryopumping will freeze out remaining material to finish the job of maximum vacuum, where the point is to minimize the material that will condense on your surfaces when you reach base temperature.

Challenges to holding a vacuum

Equally important is the continued contamination while cold. There are two major sources of contamination here – leaks at the seals and outgassing from internal materials. While classic O-rings can provide a fairly good seal, the reality is that they leak even when holding a high vacuum, and along with that come oils from the O-ring substrate and the O-ring grease used.

Another problem is contamination from internal outgassing can be from plastics or adhesives, as well as moisture captured in the surfaces of metals like aluminum and steel. Over time, these unwanted substances settle out on surfaces. This effect can be greatly reduced by baking out the enclosure before pulling the vacuum. This releases moisture and other inclusions from the surfaces in advance rather than into the vacuum environment. Some cryostats do not allow bakeout, and many cryocoolers have maximum temperature limits that prevent backout.

The fallout of these contaminants when cryopumped or frozen out on interior surfaces, can be a huge problem for researchers. In practice, these predominantly occur on your coldest surfaces. Often this is where the most important parts of your experiment occur. Foreign materials can affect resonant frequencies of optical cavities or introduce unwanted effects like surface scattering. For experiments that run for extended periods, the buildup is cumulative, so effects worsen over time and may cause your system to warm up over time. One possible temporary remediation is to warm up your sample occasionally, force off the unwanted debris, and then cool back down.

Four9 Design's Innovation

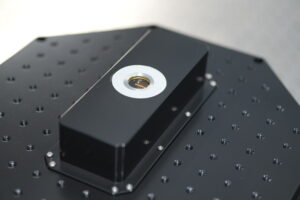

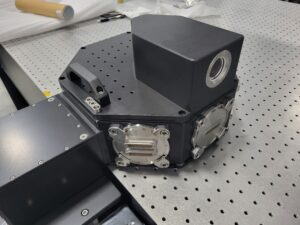

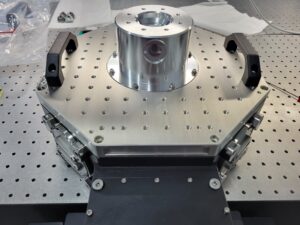

Four9 Design has a unique “chamber within a chamber” design, that puts two seal layers between your sample and the outside world. Between these seals is a manifold chamber that buffers material flow through the system.

A system designed for UHV, whether using O-ring or metal seals, must have higher performance seals and thus provide much better protection from these leaks. If an O-ring approach is taken, the rings are precision made from specialized materials and post processed to provide the best seal. We call these Os-Rings to distinguish them from low-cost garden variety O-Rings. Because of their tight tolerances, no O-Ring grease is required or ever used! This eliminates the source of these contaminants from your equipment. The use of these Os-Rings gives the user the convenience of a simple liftoff for the upper chamber, and the ability to reuse the seals (as opposed to conflat metal seals)